Collectors

The Botkin Collection and the Naïvete of the Educated Consumer

From a wealthy Russian family well known for private art collections and patronage of contemporary artists, Mikhail Petrovich Botkin (1839-1914) fashioned himself as an artist, author, art historian, archaeologist, collector, and advisor to museums and collections. He studied at the St. Petersburg Academy of Art, although his own artworks never received any serious critical acclaim. He was a member of the Imperial Archaeological Commission, consultant for the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Art at the Hermitage, and the Director of the Museum of the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, among many other roles he assumed or was appointed to in Russian art institutions and societies.

During a brief residence in Italy, Botkin collected a few pieces of Renaissance art which he brought with him when he returned to St. Petersburg. Perhaps inspired by the prestigious collections of fellow Russians Zwenigorodskoi and Basilevsky, Botkin collected with unbridled enthusiasm between 1892 and 1911. In 1892, his collection included 7 enamels, but, by 1911, his collection had grown to 162 enamels, including the 43 enamels from the Zwenigorodskoi collection, which he later sold to J.P. Morgan. Like other collectors of his day, Botkin collected paintings, sculpture, metalwork, bronzes, glass, ivories, ceramics, furniture, and textiles, but his enamels are perhaps the most well-known items from his collection, because their authenticity has long been questioned. Most of the enamels had no known history before Botkin acquired them, and they are in such pristine condition that they are unlikely to be from archaeological contexts.

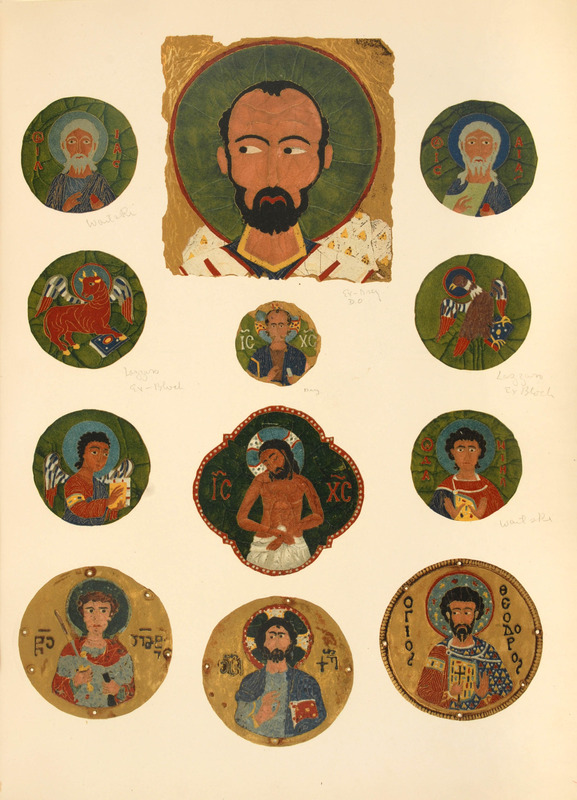

Despite the misgivings of renowned scholars such as Kondakov, Botkin published a catalog of his collection in 1911, in which it is clear that he believes his objects to be authentic Byzantine and medieval art. His catalog includes black-and-white photographs of the rooms that housed his collection, but, like other private collectors before him, Botkin chose chromolithography to illustrate individual pieces. In 1923, some items were “restored” to Georgia and the rest sold, many to private collections and museums in the United States even though collectors were uneasy about their authenticity.

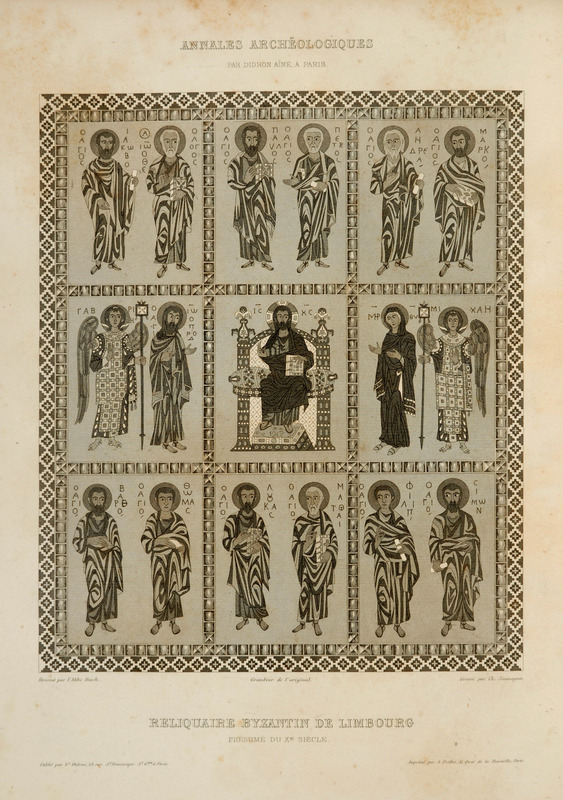

Since then, scientific analysis by the Walters Art Gallery in cooperation with Dumbarton Oaks has proven that some Botkin enamels were indeed forgeries. Research into the iconography has demonstrated that the forgers used illustrations from earlier 19th-century catalogs and published studies as models for the Botkin enamels (for example, one of the known forgeries bears remarkable similarities to the illustrations of Abbé Ibach's 1858 study on the enamelled reliquary in Limburg an der Lahn). The final “nail in the coffin” was the recent discovery of papers of a master-designer for Faberge, Franz Birbaum, who was suspicious of the Botkin enamels. Birbaum conducted a quiet investigation and discovered that one of the Faberge craftsmen, Petr Nikolayevich Popov, had been collaborating with a dealer in St. Petersburg to defraud Botkin. Popov confessed to Birbaum that approximately 150 of the 162 enamels illustrated in Botkin’s catalog were his own work.

Among the known forgeries is an enamel depicting St. John Chrysostom (1st row, center, plate 85) now in the Dumbarton Oaks collection.