Collectors

The Zwenigorodskoi Collection: Exquisite Book for Exquisite Enamels

The Zwenigorodskoi collection is almost as famous for its catalog as it was for its ancient enamels.

Very little is known of the collector Aaron Zwenigorodskoi himself. It is believed that he developed an interest in medieval art during a visit to Spain in 1864. By the end of the nineteenth century, his collection included 43 early Byzantine, Georgian, and Kievan enamels of the highest quality. At the time, his collection was considered the premier collection of Byzantine and related enamels, but now it is recognized that some of the pieces are of questionable provenance.

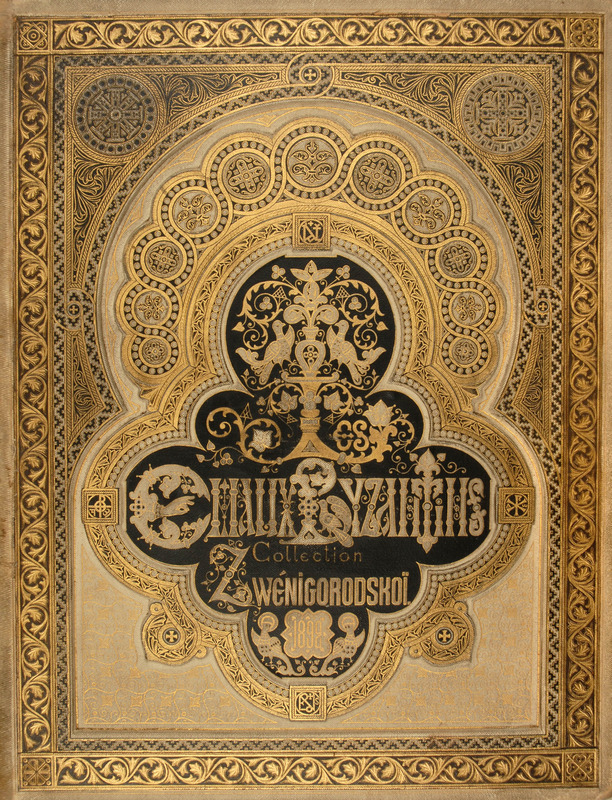

In 1890, Johann Schulz published a short article about the collection (the Dumbarton Oaks copy is inscribed by Zwenigorodskoi himself), but Zwenigorodskoi planned an elaborate catalog and study for which he hired Russian art historian Nikolas Kondakov. For the publication, Zwenigorodskoi chose not to use photographs, although the technology was available; instead, he hired expert illustrators to produce engravings and chromolithographs from photographs or examination of the objects themselves. After 8 years of work, the sumptuously illustrated and beautifully bound catalog Histoire et Monuments des Émaux byzantins appeared in 1892, but it was not available for sale. Zwenigorodskoi reportedly paid upwards of $200,000 for a limited edition of 200 copies that he gave to royal and important persons throughout Europe and Russia. Copies that he gave to personal friends include a portrait of Zwenigorodskoi as a frontispiece; the Dumbarton Oaks copy has this portrait and is numbered no. 56 in the series, but its original owner is not known.

So admired was the catalog itself that, in 1898, Vladimir Vasil’evich Stasov (1824-1906), director of the art department at the Imperial Public Library, published a book that celebrated the catalog and its reception in Europe and Russia. Stasov was an art historian, a member of the Russian Archaeological Society, and an advocate for Russian arts at home and abroad. His book reprinted statements that Zwenigorodskoi made about his own collection and catalog, letters that recipients of the catalog wrote in admiration of the work, and reviews of the catalog. Stasov also exhibited pieces of the catalog in the Imperial Public Library; illustrations of the display case are included in the book. In 1937, Eugene Golomshtok reported that the display was still one of the library’s “chief exhibits.”

In 1894, Zwenigorodskoi tried to persuade the Imperial Archaeological Commission to purchase his collection for the Hermitage, but the Commission refused. Eventually, the collection passed to N.V. Miasoedova-Ivanova, and the Russian state was offered the chance to buy the collection yet again. At the same time, American collector J.P. Morgan asked one of his dealers Jacques Seligmann to investigate quietly; Seligmann reported back that the owner refused to sell because of the interest of buyers in Russia. Ultimately, another Russian collector Mikhail Botkin purchased the Zwenigorodskoi collection, which became the core of his own collection of enamels. But Morgan continued to covet the Zwenigorodskoi collection, and, with Seligmann’s assistance, he eventually bought it from Botkin. After Morgan’s death in 1913, the collection went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

![Histoire du livre Les émaux byzantins, [collection de] A.W. Zwenigorodskoï](http://images.doaks.org/before_the_blisses/archive/fullsize/9c0ed33ff92b89b486dab3fc57e0cb6b.jpg)