Monumentality in Microcosm

1660-1860: Baroque Precedents and Beaux-Arts Exponents

The narrative of Beaux-Arts city planning is that of overlapping conversations between garden design and urban design; between France and the Americas; and between evolving interpretations of neoclassicism in the Baroque and then the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The City of Washington, D.C. bears a deep metaphorical and literal connection to the garden. From the earliest dreams of the City’s founders to the boosters of the Gilded Age, Washington, D.C. was conceived as a garden its own right (Longstreth 2002). For over two centuries, the real and imagined city of Washington has been depicted in plans, maps, and renderings as both a front yard to the nation’s vast wilderness and an arcadian setting for the seat of a new democracy. Thomas Jefferson’s own early sketches for a national capitol bear a clear resemblance to his estate Monticello – a ferme ornée or gentleman’s farm – and to the University of Virginia, both of which he designed as integrated compositions of architecture, garden, and wilderness beyond.

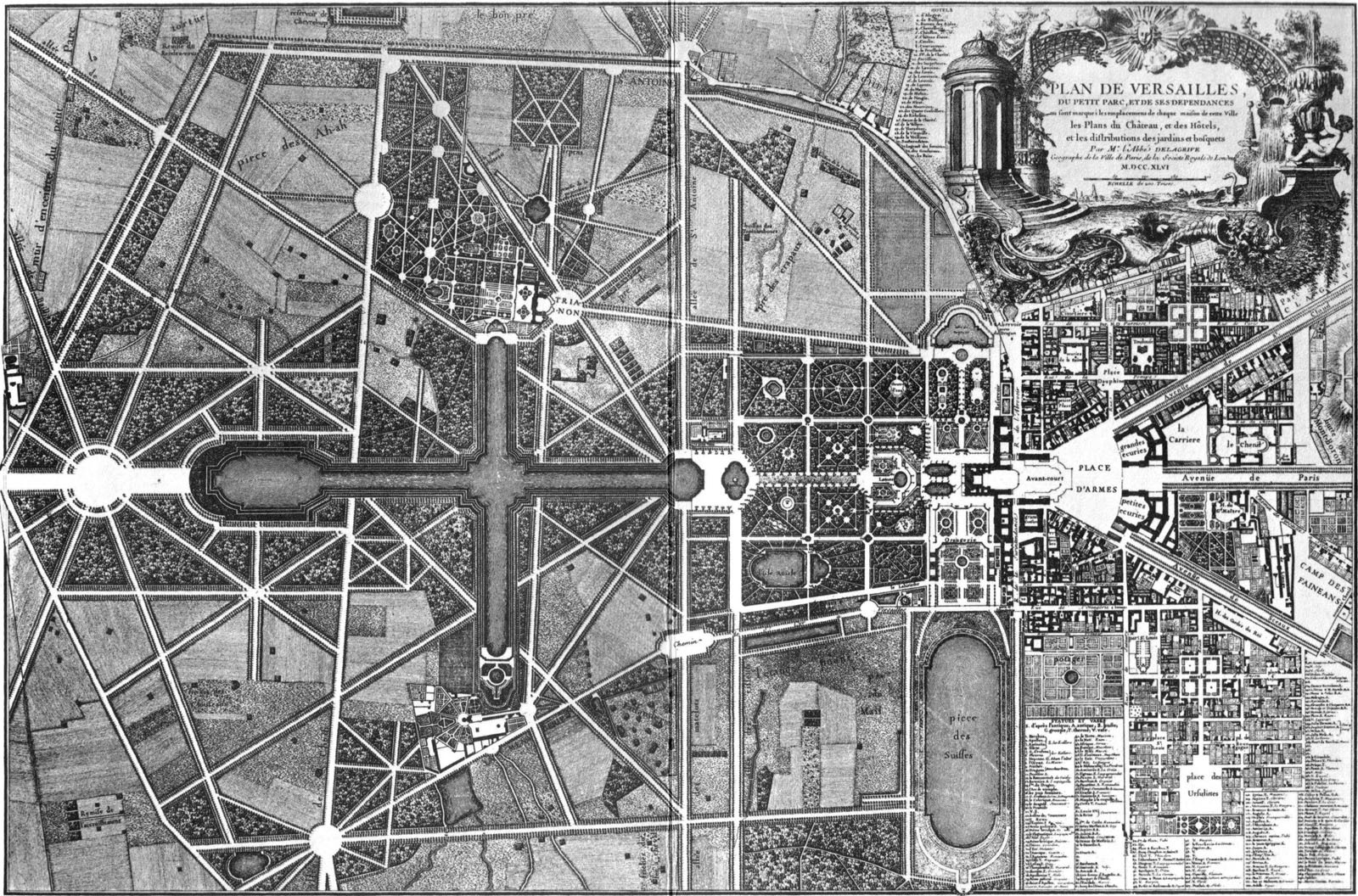

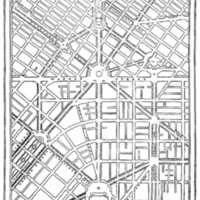

Pierre Charles L’Enfant – the originator of the Washington, D.C. plan itself – was profoundly influenced by French garden design of the 17th and 18th centuries. Trained at the Louvre in decorative art during the mid-1700s, L’Enfant had experienced the gardens at the Tuilleries; which at the time were one of the single largest redevelopments of Paris’ urban fabric. Royal gardens through the preceding century were executed at a monumental scale – equivalent to whole towns and cities – totally unprecedented in Europe. L’Enfant spent time at Versailles (designed by Le Notre), and would have studied garden designs of Saint-Cloud, Sainte Germain-en-Laye (also by LeNotre), and Marly-le-Roi (Mansart and LeBrun). L’Enfant’s fluency in the language of garden design would have included knowledge of previous – if unexecuted – redevelopment plans for London (Wren 1666) and St. Petersburg (Trezzini 1703). L’Enfant would have also known Pierre Patte’s composite plan of Paris (1765), which combined a number of proposals for locations and designs of the Place Louis XV and prototyped an emerging urbanism that connected discrete open spaces physically with straight corridors and visually with the architectural frame of a uniform street wall. In conceiving a new capitol city for the United States of America, it would have been natural for L’Enfant to design at an expansive scale, employing the concepts and devices codified in the royal gardens of France. His 1791 plan for Washington, D.C. encompassed an area of 6,000 acres, far surpassing in scope any previous city plan in the Euro-American world.

L’Enfant deployed the vocabulary – and not just the scale – of Baroque gardens in his plan for Washington, D.C. Concepts such as the controlled vista, choreographed procession, surprise, compression and release rendered forms of axial organization, allles and framed corridors, focal points of architecture and sculpture, evenly distributed open spaces, and the fractal nesting of small intimate spaces within a larger composition (Berg 2007, p14). These forms would become integral components of Beaux-Arts and City Beautiful planning in the coming centuries (Hines 1991, p81). They become clearly legible in Haussman’s redevelopment of Paris and Cerda’s plan for Barcelona during the mid-19th century. Later, the elements of Baroque garden planning come to bear upon plans for cities in America and elsewhere in the new world: San Francisco and Chicago (Burnham 1904 and 1909); Argentina (Thays and others, 1880s-1920s); New Delhi, India (Lutyens 1910); and Canberra, Australia (Griffins 1911).